I write today in sadness and frustration.

I hesitate to link to Blake Ross’ recent article on the tyranny of Wealthfront because it strikes a blow that sets my friends’ and generation’s investment goals back immeasurably. While I fear his colorful writing and celebrity status will likely confuse people into inaction, I hope this article will inspire you to action and shed light on some the inaccuracies and misrepresentations in Ross’ article.

Before I begin my response, I implore readers: If you’ve been evaluating Wealthfront, Betterment, Vanguard Retirement Funds, or Schwab Intelligent portfolios over the last few months (or years) and can’t decide which to use — for the love of whatever you believe in, stop reading this post, roll a 1d4 and just pick one. They’re all better (by a large margin) than you leaving it in your checking account, spending it on something stupid, or giving it to an expensive active advisor. Go. Do it. Now. Which one did you choose? As the Rock would say, “it doesn’t matter [what you chose, as long as you chose].”

Time for business.

There is a lot of glossy rhetoric in Ross’ post and while I appreciate the passion and his renegade approach, I am upset by the misinformation. I’ll distill the rhetoric down to the key arguments and address those.

Argument A: You’ll make more money with Vanguard Retirement Fund than a Roboadvisor – This is a strong claim that in Ross’ words, “There is simply no evidence, nor any theoretical reason, to believe”. It’s the hardest claim to prove but is also most important of the arguments. Simply put, the Wealthfront portfolio costs slightly more (quantified below) annually but probably makes up for this difference and then some due to tax loss harvesting (enough to close the gap alone), a likely superior asset allocation, a likely superior rebalancing strategy, and a faster rate of innovation.

Argument B: Roboadvisor fees increase over time – This isn’t a particularly unique thing, and I’m not sure what the ultimate impact is of this argument, especially since Ross’ alternative suffers the same “flaw”. A number of business models include fee structures like this, especially when the benefit of the product increases over time as well. The fee does not rise on a percentage basis, but only on an absolute basis, and only if the Roboadvisor is making you money.

Argument C: Tax-loss harvesting is too good to be true and the benefit is overstated – Ross agrees that there is an aftertax benefit to tax loss harvesting. His argument is that the magnitude of the impact is too small to matter. Unfortunately, even if we cut Wealthfront’s estimates by 10x and then refer to Ross’ citation about Tax Loss Harvesting, both sources claim an annualized benefit of at least 0.20%, which is already enough to push Wealthfront above Vanguard Retirement Funds. Finally, the author of Ross’ only substantive claim against the benefits of Tax Loss Harvesting actually supports Roboadvisors, and even Wealthfront specifically.

Argument D: Roboadvisor fee structures are unprecedented – No they’re not.

Note that while Ross decides to aim his critique primarily at Wealthfront, his arguments apply to Roboadvisors at large and so I’ll genericize my response where I can. When I use specific fee figures, I’ll use Wealthfront’s. Also note that Ross’ alternative is by no means bad, it’s just not better, and certainly not better to the degree that justifies the tone of his critique. I love Vanguard. They’re great.

Onward…

A. You’ll make more money with Vanguard Retirement Fund than a Roboadvisor

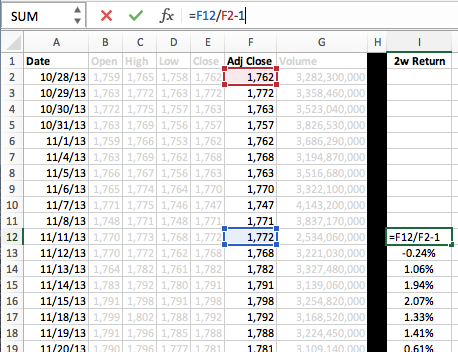

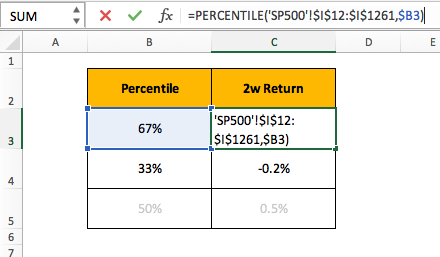

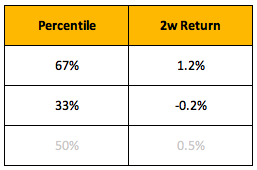

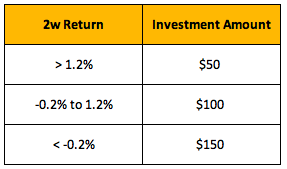

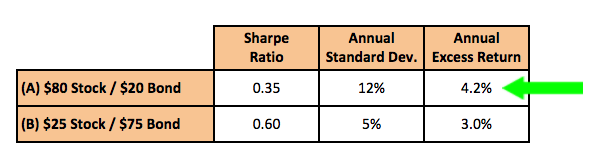

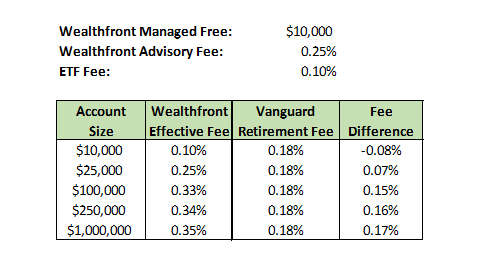

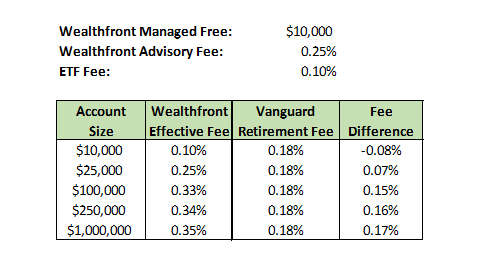

1. The true fee difference is at most 0.17% in Vanguard’s favor, likely less – Ross overstates the cost difference between Wealthfront and Vanguard. Wealthfront’s portfolio costs at most 0.35% annually (closer to 0.33% for accounts with Direct Indexing). This fee is composed of a 0.25% fee paid to Wealthfront and a 0.10% fee paid to the administrators of the ETF that Wealthfront invests you in (mainly Vanguard, by the way). Ross’ “dirty secret” alternative (Vanguard Retirement Fund) charges 0.18%. Below is a comparison of total expenses for Wealthfront vs a Vanguard Retirement portfolio. Wealthfront manages $10,000 for free and adds an extra $5,000 managed for free for every client you refer to Wealthfront, reducing your blended costs. The table below assumes the minimum of $10,000 managed for free.

Now, that means we need to see if Wealthfront can overcome 0.07% – 0.17% in annual fees. Let’s get to work.

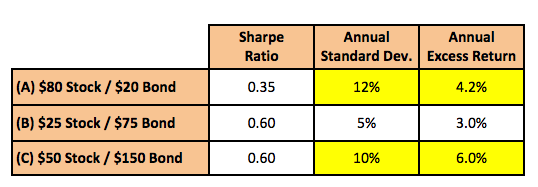

2. Tax Loss Harvesting by itself makes up for the difference and then some – Wealthfront claims Tax Loss Harvesting can add approximately 1.29% annually (2.03% if one includes tax-optimized direct indexing). While I agree with Ross that this figure is huge and potentially overstated, there’s (a) no evidence he provides to the contrary and (b) just ignoring it is hardly sensible. So even if we decimate Wealthfront’s claim, we get to a 0.20% benefit from TLH with TODI. So this means that 1/10th of Wealthfront’s claimed Tax Loss harvesting makes up the fee difference by itself, and then some. I contend that Ross’ arguments show a misunderstanding of what TLH is and the mechanics of how it works. I’ll dive into this in depth in the TLH section.

3. Ross likely misrepresents Buffett’s viewpoint – Furthermore, he mis-characterizes a Buffett quote as evidence to assail robo-advisors: “… Put 10% of the cash in short-term government bonds and 90% in a very low-cost S&P 500 index fund. (I suggest Vanguard’s.) I believe the trust’s long-term results from this policy will be superior to those attained by most investors — whether pension funds, institutions or individuals — who employ high-fee managers.” First, if you asked Mr. Buffett whether 0.37% is a high-fee manager, I’d wager he wouldn’t think it was too bad given the management fees being in the 1-2% for most of his lifetime and given Ross’ own argument that WF has significantly lower fees than other advisors and given that Ross’ alternative has fees that are less than 0.20% lower. Second, I’d also place a wager that Buffett is referring to active managers (most Roboadvisors are passive asset allocators). Third, Wealthfront disputes Ross’ claim directly in an article that compares the Wealthfront portfolio to Buffett’s recommendation. Finally, Buffet’s allocation is obviously an oversimplification that can and should be improved upon. Or is it? Let’s see what the experts have to say about the importance of a diversified asset allocation.

4. Asset Allocation matters a lot – In a seminal 1985 paper it is argued that asset allocations explained almost 94% of a portfolio’s return versus other factors contributing 6%. The administrators of Mr Ross’ alternative also believes this too as evidenced by a Vanguard-published paper stating that almost 77% of portfolio performance comes from asset allocation decisions (they removed some factors from being classified as asset allocation that the Brinson paper includes). If academics don’t convince you, fine.

5. Good investors also think asset allocation matters a lot – Some not-so-bad investors say stuff too. “Asset allocation is critically important; but cost is critically important, too—All other factors pale into insignificance.†-John Bogle, founder of Vanguard. “The most important decision you will probably ever make concerns the balancing of asset categories (stocks, bonds, real estate, money market securities, etc.) at different stages of your life.†-Professor Burton Malkiel, author of A Random Walk Down Wall Street, way before he became Wealthfront’s CIO. “Choose your asset allocation model carefully. Asset allocation is the biggest factor in determining your overall return.†-Charles Schwab.

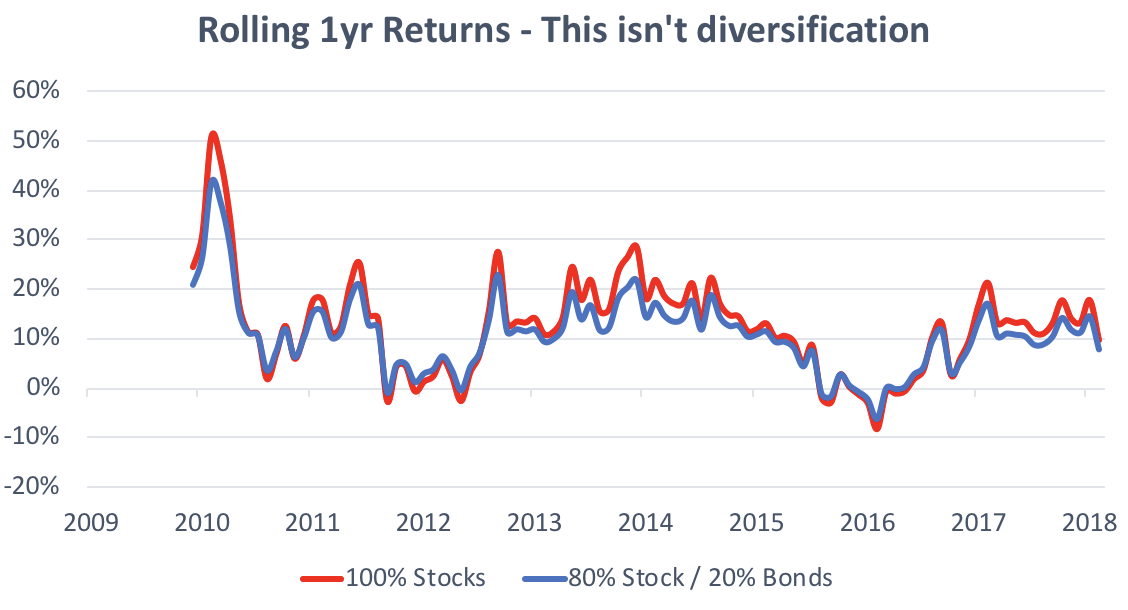

6. Figuring out asset allocation difference is hard, we have to evaluate it systemically – Now, the question is whether Wealthfront’s asset allocation is better or worse than the Vanguard retirement fund’s. This is a very, very tricky question to answer because there’s really no concrete way to know aside from just seeing how they perform. The issue with that approach is you don’t know systematically which (if either), will outperform. You only know what actually happened, which is significantly influenced by chance. What we can do, however, is understand the process each manager employs to see if there are systematic biases to outperform the other or not.

7. Vanguard portfolios are more constrained than Wealthfront’s – Vanguard’s Retirement portfolios use their own funds. Wealthfront has no such requirement. That means that in cases where an asset allocation would be better served by having a non-Vanguard fund that provides a certain set of exposures, Vanguard must find a close proxy, create a new fund, or risk underperformance. Wealthfront has the opportunity to find the best alternative (which happen to be Vanguard MOST of the time). It’s tough to quantify, but the argument is simply that a constrained portfolio is likely worse than a less constrained one.

7. Wealthfront’s rebalance strategy is likely more sophisticated than Vanguard’s -Furthermore, Wealthfront’s rebalance strategy is optimized to minimize drift while keeping costs at bay, a strategy advocated by Vanguard. While Wealthfront has developed software to assess the trade-off between these two sides in real time (it operates continuously), Vanguard does it daily (because they receive fund inflows and outflows daily) incurring small costs on the fund each time and requiring discrete decision-making which is not real-time. Additionally, there is evidence to believe that Vanguard uses time-based and threshold based triggers, which they admit in their own white paper have issues. While the impact here is likely small, it is yet another systematic benefit to an automated strategy like Wealthfront’s.

8. Wealthfront’s rate of innovation is fast – Finally, Wealthfront has been at the Vanguard (see what I did there?) of change in the industry for a long time. I will say that Vanguard’s innovations are great, but Wealthfront has been the Roboadvisor that has consistently pushed the envelope, developed new strategies, reduced cost via cheaper ETF’s, and made more features available to smaller investors faster. Others follow suit of the star-studded investment team from Wealthfront. Purely on a trust basis, I would trust the investment analysis (I’ve verified enough myself) of Wealthfront. Even beyond that, there’s a tangible benefit being the leader of innovation because your investors realize the benefits of the features while investors in other funds must wait for the innovations. Wealthfront discusses this specific argument here.

9. Ross’ critique minimizes the impact of human psychology (and lack of logic) on financial decisions – Ross says, “If you open a retirement account, and you invest some of your paycheck each month into a Vanguard Target Retirement Fund, and you just…leave it… until retirement… you don’t do anything when the folks on CNBC announce that the sky is falling; you don’t do anything when Cousin Eddy calls from a secure underground bunker in the badlands and says that the fed is printing money and it’s time to liquidate and ammo up; you don’t think it’s a sign that your parrot said “fuhgeddaboutit†but you thought she said “get a nugget†and surely that must mean a gold nugget? and you looked online and noticed that the price of shiny yellow metal was crashing and wait your parrot is also yellow and I’ll be damned if that isn’t a sign to buy… no, if you just leave it there to compound over decades… then you will probably make more money than … if you used Wealthfront.” That’d be nice, but it rarely happens. The story of Peter Lynch and the Magellan Fund is a cautionary tale. He ran the Fidelity Magellan fund for 13 years and achieved a ~30% annualized return. The average investor in the fund, however, actually lost money. This happened because investors would fear on the dips and sell and chase returns after a big run up. They essentially broke the cardinal rule of investing by selling low and buying high, over and over again. An automated advisor protects you from yourself marginally more than a portfolio you need to manage more (or even a Vanguard Retirement Fund which is psychologically easier to view as a single investment rather than money with an advisor).

10. Vanguard Retirement Funds are either less tax efficient (in taxable accounts) or they are less optimized (in non-taxable accounts) than the Wealthfront portfolio — Wealthfront offers different asset allocations for taxable and non-taxable accounts in order to optimize tax treatment. The Vanguard Retirement Fund is a single entity that holds a single asset allocation is not individually optimized for one type of account or the other. The impact of this is non-negligible.

B. Roboadvisor fees increase over time

1. Yes, they do – But only if they make you money. There doesn’t seem to be a differential implication presented.

2. It’s pretty common – In fact, many businesses (even those not on Wall Street) have a business model that charges increased fees based on usage. Many SaaS companies charge by seat. Many data businesses charge by volume of data processed/stored. There seems to be no distinction drawn between Roboadvisors and these other businesses.

3. Vanguard’s got the same “issue” – In fact, the suggested alternative (Vanguard Retirement Fund) charges exactly the same way.

4. What do you believe? There’s a philosophical / value-based question on whether you think the fee should be proportional. If the value being provided is proportional (it is for many SaaS companies, and it is for Wealthfront too), then I personally find it fair to charge a fee in this way. You’ll have to figure out for yourself what you believe on this one.

5. The structure aligns incentives – Furthermore, Wealthfront is better than a number of the alternative subscription-based models in that the fee only increases if your outcomes improve (portfolio value increases). SaaS models that charge by seat cost you more as your # of seats grow, but don’t cost you less if the seats do dumb things with the product or if the seats use the product less. It’s incentive alignment, not predatory pricing.

6. Ross misrepresents rarity of the model – He argues, “It’s not just that Wealthfront charges users for its software, which is rare.” This one made me angry so I had to take a break to watch Netflix and listen to Spotify before coming back to blog on my personal domain. He also argues, “It’s also that, on average, Wealthfront increases its subscription fee every day.” Yes, I agree. But the question is whether you are OK watching your investment balance grow by $100 while watching the fee grow by $0.25. If you’re not, then I ask about the alternative. His alternative is structured similarly.

7. Roboadvisors are not merely providing advice – Finally he says, “Stop charging proportional fees for advice,” to which I say Roboadvisors provide more than merely advice. They provide services like trading for you, keeping up with changes in ETF fees and landscape, rebalancing intelligently instead of periodically, tax loss harvesting and performance tracking. As mentioned earlier, a number of the services above have benefits that in fact do scale with the size of the account. The implication of the statement above is that one should pay fixed fees but gain bigger benefit over time from those fees.

8. Wealthfront has never been profitable – In response to the “Wealthfront helps itself to such margins” argument, it is important to note that the company is not profitable and won’t be profitable any time in the next few years. You can write that in pen. On the 2bn they manage, they’re revenue is less than $5mm. They’ve lost money for every year they have been in existence. Vanguard runs at cost, according to Ross’. I’d prefer to let the VC’s subsidize me.

C. Tax-loss harvesting is too good to be true and benefit is overstated

1. We need to save in taxable accounts too – Ross argues that “If your nest egg exists entirely in a retirement account, as it does for many Americans, then tax loss harvesting won’t help you at all.” While this is true, I’d argue that it is a big deal that Wealthfront is providing incentive (TLH) to invest outside retirement accounts, given the dire state of savings rates in our generation.

2. ETFs have capital gains too – With Ross’ argument that “If you practice the kind of investing that Wealthfront itself evangelizes — buy-and-hold, passive, rational, long-term indexing that is rebalanced with new money or in retirement accounts — then you should not be realizing capital gains regularly anyway.” he fails to mention that his alternative also recognizes capital gains regularly. Most ETF’s distribute capital gains at the end of the year and do not harvest losses, so you’re basically paying capital gains taxes in either scenario. Furthermore this cuts against Ross’ argument that tax loss harvesting gains are capped while Wealthfront’s fees are uncapped.

3. Even rudimentary TLH is enough for Wealthfront to come out on top – Furthermore, Ross’ argument against Tax Loss Harvesting as made by the Kitces article above actually says that 0.20% improvements are based upon lumpy and dumb harvesting (once/year, at the end of the year) versus a much more sophisticated, real-time algorithm employed by Wealthfront.

4. Ross’ own citation makes a pretty strong case for Roboadvisors – The same author who Ross cites also writes a pretty good article about How Declining Transaction Costs And Robo-Indexing Could Disintermediate Index Mutual Funds And ETFs.

D. Roboadvisor fee structures are unprecedented.

No they’re not.

Conclusion

Invest your money in low cost ETF’s. If you have a taxable account and don’t want to spend time on it, I recommend Wealthfront. If you don’t have a taxable account and have time, you can mimic Wealthfront’s allocation and rebalance yourself. You can pick Betterment. You can pick Wise Banyan. You can pick Schwab Intelligent Portfolios. You can pick Vanguard Retirement funds. Do something with your money. But please don’t be paralyzed into inaction by rhetoric. The Roboadvisors will also help you avoid destructive cognitive biases.