The big deal about Risk Parity

On the heels of Wealthfront’s recent announcement of a risk parity offering there has been renewed interest in this decades old concept. In this first post of a series about Risk Parity for personal investing I’ll provide a primer on the strategy and why it is a big deal.

Risk parity says we should allocate our risk, not our capital

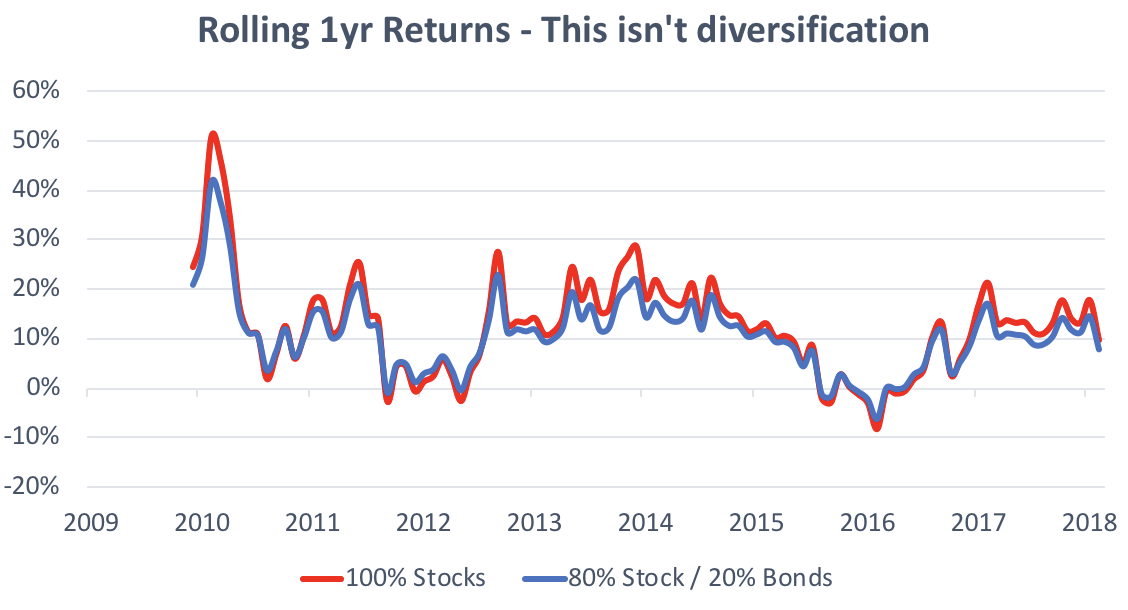

Risk parity is a concept that suggests investors allocate assets based on their risk, not merely the capital allocation. A simple, common asset allocation is $80 stocks and $20 bonds. Stocks are on average 2-4 times as risky as bonds. As a result, while the share of capital is 80% stocks and 20% bonds the share of risk is closer to 95% stocks and 5% bonds. Lamest diversification ever.

Risk parity portfolios are based on the premise that allocating capital doesn’t accurately reflect the risk of the assets in the portfolio. Risk parity, not capital parity.

Risk parity has higher allocation to lower risk assets like bonds

Bridgewater Associates pioneered the risk parity strategy through their famous All Weather Portfolio in the 1970’s. Since then, various implementations of the concept have been brought to market by other asset managers like AQR and Putnam. Essentially, these implementations all have larger capital allocations to bonds and lower capital allocations to equities than standard portfolios to more evenly divide the risk in the portfolio.

Risk parity trounces standard portfolios on return/risk ratios

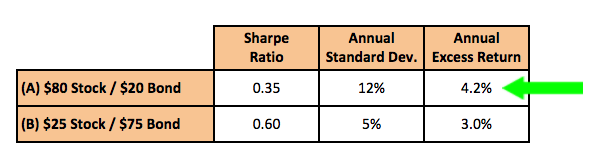

This is a big deal because a risk parity portfolio’s risk-based diversification offers higher returns versus the standard portfolio at equal levels of risk. A standard portfolio might achieve a 0.3 – 0.4 sharpe ratio (great primer), meaning that it provides 0.35 units of return for each unit of risk. For an average portfolio with an annualized standard deviation of 10%, this is a 3.5% annual excess return over cash. A well-managed risk parity portfolio on the other hand can deliver a sharpe ratio between 0.5 and 0.7 which translates to a 6.0% annual excess return.Note: To me the assertions here are supported by substantial evidence, but there are still smart people who will disagree with some of them. I’ll dig into some of of the assumptions in future posts.

Not everyone has access or ability to do risk parity

There are two reasons why this strategy isn’t far more widely used. First, not all investors have access to leverage and this strategy usually requires it. Second, professionally managed portfolios are expensive and/or have high minimums.

A standard $80 stock and $20 bond portfolio (Portfolio A) would return ~4.2% (12% volatility x 0.35 sharpe ratio). On the other hand, a $100 portfolio with equal stock and bond risk is $25 of stocks and $75 of bonds (Portfolio B) has a puny annual volatility of about 5%. This portfolio would return ~3% (5% volatility x 0.60 sharpe ratio). Since 4.2% is higher than 3% *and* 12% is acceptable risk for most under the age of 40, investors choose Portfolio A with a higher return.

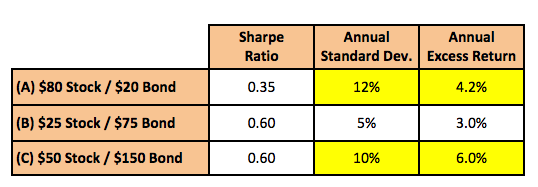

Leverage (borrowing money to purchase securities) can double the excess return and risk of Portfolio B (200% leverage). We’ll achieve this by borrowing $100 and using it to buy another $25 of stock and $75 of bonds. This is new Portfolio C is $50 stocks and $150 bonds. Despite the use of leverage, it still has lower risk (10% vs 12%) and provides better returns (6.0% vs 4.2%).

Leverage lets us take superior, diversified portfolios and increase or decrease their risk to our desired level. We get more return for each unit of risk we take by doing this.

[yop_poll id=”1″]